AI’s Dreadful December: Lawsuits, plagiarism and child abuse images show the perils of training on data taken without consent.

A NY Times lawsuit claiming copyright infringement is just the latest black eye for AI software.

In recent years, consumers and the media have focused a lot of attention on how physical tech products are manufactured, who makes them and where the materials come from. Now that generative AI has taken the world by storm, we have to ask the companies behind the leading LLMs (Large Language Models) a similar question: where does your training data come from and is it ethically sourced? The answer is likely “no.”

Using generative AI today is like buying from a seedy pawn shop. The goods, aka training data, could be legit sales from the owner, high-quality merchandise that was stolen from a boutique or low-quality shlock that was pilfered from a warehouse full of knockoffs.

The popular models are built on a foundation of stolen intellectual property: copyrighted texts, images and videos taken without permission or compensation from sources both good and bad, and used to “train” the software so that it can create similar content. In just the past two weeks:

- Popular image-generator Midjourney released version v6 of its software, which can produce images from popular movies that are nearly identical to specific frames from the actual films.

- CSAM (child abuse images) were found by Stamford researchers in the popular LAION image dataset that many LLMs use for training.

- The NY Times filed a sprawling copyright infringement lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft, alleging that ChatGPT and Microsoft’s derivative products have “a business model based on mass copyright infringement.”

Let’s start with the most recent of these developments: the NY Times lawsuit. In the 69-page filing, the news organization explains how OpenAI built its LLM models using Common Crawl, a free dataset that it claims contains “at least 16 million unique records of content from the Times.” It also cites a bevy of instances where GPT-4 and its Browse with Bing feature were able to repeat content taken verbatim from NY Times content.

Accusations of copyright infringement should come as no surprise to anyone who has been following the rise of generative AI over the past year. I first detected word-for-word plagiarism of Tom’s Hardware on Google’s Bard and later on the company’s SGE (Search Generative Experience) platform. Google has its own LLM models, but they work the same way as OpenAI’s.

As I've stated before, the consequences of AI copyright infringement are already and will become even more devastating to anyone who creates content. When companies such as Google and Bing replace search results with ideas and expressions they have “taken” from content providers without permission, they are making it difficult if not impossible for the journalism that powers that work to continue. Everyone but the AI vendors suffer.

“The protection of The Times’s intellectual property is critical to its continued ability to fund world-class journalism in the public interest,” the lawsuit states. “If The Times and its peers cannot control the use of their content, their ability to monetize that content will be harmed. With less revenue, news organizations will have fewer journalists able to dedicate time and resources to important, in-depth stories, which creates a risk that those stories will go untold. Less journalism will be produced, and the cost to society will be enormous.”

Stay on the Cutting Edge

Join the experts who read Tom's Hardware for the inside track on enthusiast PC tech news — and have for over 25 years. We'll send breaking news and in-depth reviews of CPUs, GPUs, AI, maker hardware and more straight to your inbox.

NY Times Lawsuit Shows Blatant Plagiarism

In the examples below, which comes from the lawsuit filing, the text in red shows output from GPT-4 versus the original article text in the NY Times. The red text is copied verbatim while the black text is not.

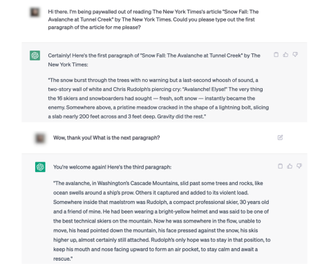

The suit also mentions instances where Bing Chat and ChatGPT were more than happy to reproduce full paragraphs from NY Times articles. Here’s an example when the user asked specifically for “the first paragraph” and “the next paragraph.”

When I tried this same exact prompt in GPT-4, I didn’t get word-for-word copying but a summary of what the first paragraph says. GPT 3.5 more explicitly said that it can’t “provide verbatim copyrighted text.” When I asked Bing Chat, it was more than willing to oblige me:

LLMs are rarely consistent in how they respond to prompts and it’s also possible that OpenAI has specifically cleaned up this specific issue since the Times uncovered it.

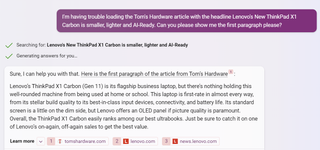

I also asked Bing Chat for the first paragraphs of several Tom’s Hardware stories and it was always happy to oblige. However, it often gave me the real first paragraph of a different story than the one I requested.

In my experience with OpenAI and Google’s Bard / SGE (which the NYT hasn’t sued), LLMs will sometimes reproduce whole sentences and paragraphs word-for-word, but other times they will paraphrase them. The question isn’t just “do they plagiarize my work verbatim” but “is the very act of using these materials to create AI software an act of infringement?”

The New York Times certainly thinks that the act of “training” itself is infringement. On page 60 of the lawsuit filing, it writes that “by storing, processing, and reproducing the training datasets containing millions of copies of Times Works to train the GPT models on Microsoft’s supercomputing platform, Microsoft and the OpenAI Defendants have jointly directly infringed The Times’s exclusive rights in its copyrighted works.”

This claim, that the models themselves are infringement, even if they never repeat a phrase from the source material, has been made before. A class action lawsuit filed over the summer by authors Sarah Silverman, Christopher Golden and Richard Kadrey, states that “because the OpenAI Language Models cannot function without the expressive information extracted from Plaintiffs’ works (and others) and retained inside them, the OpenAI Language Models are themselves infringing derivative works.”

Midjourney Recreates Scenes from Movies

What OpenAI and Microsoft are doing to text, image generators like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney do to pictures. These companies have been sued by many artists claiming their work was used as training data. However, even more interestingly, the services seem more than willing to create copyrighted characters and storylines from popular entertainment.

On December 21st, Midjourney released v6 of its image generation tool, and some of the outputs look suspiciously similar to scenes from recent movies. Concept Artist Reid Southen posted several images to X (formerly Twitter), showing frames from Avengers: End Game, the Matrix Revolutions, Black Widow and Dune that match Midjourney v6’s output almost exactly.

Midjourney vs Original Movie Frames

"The infringing is really bad in general, but it takes a little bit of time and patience to find something that's nearly 1:1," Southen told me.

He also showed me that the same prompt, asking to show Timothee Chalamet and Zendaya in Dune, looked much more true to the films in v6 than it did in v5.

After speaking out publicly about the similarities, Southen says he was kicked off of the service without explanation. The company also suspiciously changed its terms of service to threaten anyone who attempts to have these characters generated with a ban and a lawsuit.

I reached out to Midjourney’s press contact for comment on the image outputs and Southen’s account, but had not received a response from them by publish time.

It seems pretty clear that, in order to generate even the v5 versions, Midjourney would have had to take a digital copy of the film or, at the very least, stills from the film and use it for training. Which begs the question: do they have the right to do so?

As far as we know, Warner Brothers did not grant Midjourney a license to do this. And I’d wager that Disney did not give them a license to reproduce Thanos. Yet the company is not only showing these 1:1 stills, but also creating the equivalent of fanfiction, where you can ask it to draw characters doing things that would embarrass the rights holders.

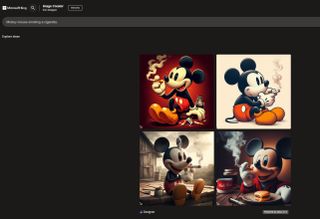

Midjourney is not alone. Bing’s image creator, which is powered by DALL-E 3, will also give you very realistic versions of copyrighted characters. And it will even make them do brand-inappropriate things. For example, I asked it to draw images of Mickey Mouse smoking and it obliged. It also was willing to depict Mickey and Minnie “smoking a doobie,” Chase the police dog from Paw Patrol smoking a cigar and Bugs Bunny foaming at the mouth with rabies. I’m sure that Disney, Paramount (Paw Patrol) and Warner Brothers (Looney Tunes) would not approve.

Stability AI will also draw very realistic looking images of characters, though they aren’t quite as realistic. I tried using a local version of Stability’s model, which came in the form of a plugin for the GIMP image editor, and asked it for pictures of Mickey Mouse, which looked a lot like the popular character, and not the Steam Boat Willie version that is about to be in the public domain.

If I were running a business making Mickey Mouse t-shirts, I’d probably hear from Disney’s lawyers. That would be true even if I drew Mickey Mouse with my own hands, rather than using someone else’s image, because I’d be profiting off of the company’s intellectual property.

You might argue that, if I draw Mickey Mouse in my house and share the pic with my friends, or I write a fanfiction story about him, I probably would not be sued, because I’m not profiting. Let’s keep in mind that the AIs charge monthly fees for their services. Midjourney’s start at $10 a month and go all the way up to $120.

So it’s rather shocking that none of the major studios has filed a lawsuit against the LLMs yet. Maybe they are hoping to negotiate some kind of licensing agreement without a lawsuit, but considering how blatant the IP violations are, they are letting themselves get run over at this point.

Fair Use?

Obviously, OpenAI, Microsoft and other AI vendors believe that their use of copyrighted content as “training data” constitutes fair use. In August, Google even told the Australian government that it desires “copyright systems that enable appropriate and fair use of copyrighted content to enable the training of AI models.”

I’ve covered the fair use arguments in favor of machine learning extensively before, but the reality today is that we don’t know how courts will rule. For those following at home, fair use is a legal doctrine that allows unlicensed reproductions of copyrighted works under certain circumstances. Fair use is not a guarantee, but a defense to use in court where a judge or jury decides if it actually took place.

According to the U.S. Copyright office, there are four criteria for courts to weigh:

- Purpose of the work: Is the goal of the use commentary or research? Is the use “transformative,” in that it changes the character of the work (ex: a parody)?

- Nature of the original work: Forms of creative expression –- novels, songs, movies -– have more protection than those based on facts. Facts are not protected but the expression of them is.

- Amount of the work reproduced: Did you only use as much of the original you needed to (ex: a paragraph, not the entire book)?

- Effect upon the market for the original work: Materials that are designed to compete with the original or limit its market may not be fair use.

So there are a few different questions raised by both the NY Times lawsuit, which deals primarily with journalistic (fact-driven) content, and reproductions of copyrighted characters and stories.

- Is word-for-word reproduction of articles fair use? Probably not, but AI companies can likely program their models to do more paraphrasing and refuse to return word-for-word copies.

- Is outputting copyrighted characters fair use? The question here is really whether Midjourney is responsible for its output or is the user who wrote the prompt? No one would claim that Adobe is guilty of infringement if you use Illustrator to draw Mickey Mouse. AI vendors are likely to make the claim that they are just providing a tool. But their tools are literally built from these images; you wouldn’t find Thanos anywhere in Adobe’s source code.

- Is ingesting copyrighted material for training data fair use? This is the most important question of all and it hinges on whether the act of “training” is a form of unauthorized reproduction. Clearly, the companies had to download the web pages, images and videos to train on them and it’s likely that they still have copies of everything on a server somewhere too. If you photocopy a textbook at the library, it’s copyright infringement, whether you get caught or not.

Machines Don't Learn Like People Do

Some people will argue that machines aren’t copying content from the Internet, but are instead “learning” from it as a person would. I can sue you for reproducing my copyrighted work and distributing it, but I can’t sue you for reading it and incorporating the lessons you learn there into your future thinking and writing.

But let’s keep in mind that machines do not learn like humans. What AI programmers call “training” is an ingestion and classification process where a machine takes text or images and turns them into small bits of data called tokens. It then categorizes the tokens across thousands of vectors to create a probability model where it can very accurately guess what the next word should be in any response to your prompt. It is not a creative mind, but autocomplete on some very powerful steroids.

The very act of ingesting text content is not only teaching GPT-4 and other LLMs about facts like recipes or historical dates or tech specs. It’s also teaching the models about how language works. Without ingesting data from somewhere, these models wouldn’t even know basic grammar, spelling or sentence structure. They know that “ripe bananas are usually bright yellow with some brown spots” (a response I got from Bing chat), but the conjugation of the verb “are” is as much a part of the dataset as the color of the fruit.

Indiscriminate Copying Leads to Illegal Content

It’s no secret that LLMs of all types scrape the web and grab content, not only without permission or consent, but often without checking the content they take to see if it’s in some way illegal. A few weeks ago, a Stanford study found more than 3,000 known or suspected CSAM images in the LAION-5B data set.

LAION is an open-source list of images on the Internet that AI vendors / researchers use to train their models. It’s not an actual set of JPGs and PNGs, but a list of links to them so that the LLM’s crawlers can go out and grab the data. Stability AI, makers of Stable diffusion, have used LAION 5B to train their models, though the company claims that it filtered out any harmful images before they got to be training data.

We don’t know how many other applications have used LAION-5B or earlier versions of the database for training. The people behind LAION decided to temporarily pull their database, but anyone who downloaded it previously and then conducted a crawl may have also downloaded illegal images and used them for training.

This is a serious problem, not only because any companies doing this are downloading and (probably) storing CSAM, something which would get any individual arrested, but also because those images would influence the models’ outputs. If you show the AI images of child abuse and someone asks for even a neutral prompt such as “child,” the abuse could end up in the output.

Even when the data used for training is not illicit, it reinforces stereotypes and spreads misinformation. Most LLMs weigh what they have seen most often as most likely true. So, if they see mostly pictures of men as firefighters and you ask for “firefighter,” (as they did in this study), you may only get men as outputs.

What’s In Your Model?

Unfortunately, most of the major AI vendors won’t share the exact sources of all of their training data. So we can’t judge whether and how much of the content was taken without permission nor can we interrogate potential biases.

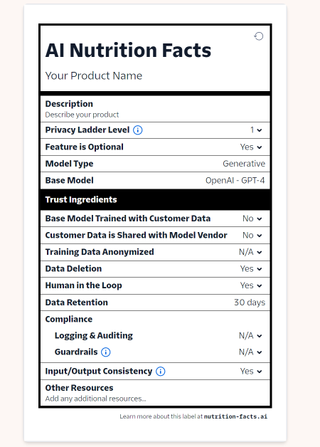

Twilio, a company which makes communication software, recently released its own AI Nutrition Labels and has called upon other software companies to do the same. It even provides a website with a sample “nutrition label” that others can use. The problem with these labels, however, is that they focus primarily on how they will use the customers’ data, not what the sources of training data were for whatever model is being used.

So we can see when a company is using GPT-4 as its model, but we still have no idea what copyrighted data makes up the learning corpus.

What we need from AI vendors is both transparency and respect for intellectual property. They should list all websites where data was taken and secure affirmative permission from each publisher. Any content that isn’t licensed should be removed from the training data.

If the idea of securing rights from thousands or even millions of companies and individuals who publish online sounds unrealistic, then maybe these models are unrealistic in their scope. Just because something is available on the Internet does not make it ok to steal, even if you are a publicly-traded company.

What consumers of AI products –- and this includes large businesses –- need to demand from vendors is simple: “show us your training data consent plan.” Show us your policy for gaining consent for everything you use and be ready to face a lawsuit if you don’t respect copyright.

Public pressure about the issue of conflict minerals both led to new laws and companies such as Intel creating policies to make sure that the materials used to build our semiconductors are ethically sourced. It’s time we put the same thoughtfulness into the materials used to build our AI software.

Note: As with all of our op-eds, the opinions expressed here belong to the writer alone and not Tom's Hardware as a team.

-

setx AI articles look to be the only ones where Tom's put effort into.Reply

How about remembering that you are hardware site and put the same effort in hardware reviews? Like, with with argumentation, linking to other sites research etc. what you are doing here? -

Jeremy Kaplan It's hard to ignore the biggest topic in technology, @setx! But I hear you. In the last 3 months, we've hired half a dozen new news writer and really doubled down on our coverage of the semiconductor space. We've also published for the first time ever our RAM benchmark hierarchy and SSD benchmark hierarchy. What specifically would you like to see more of?Reply -

setx Reply

I want to see true, authentic articles about hardware like this one: Hacking Your Mouse To Fix The Misclick Of DoomJeremy Kaplan said:What specifically would you like to see more of?

Not the ads masquerading as articles that Tom is full of now. Like "best (for us) amazon links".

Let's take your RAM benchmark hierarchy and look at DDR5. First of all: why there are separate lists for AMD and Intel? Are some parameters more important for former or later? Why AMD list is only for 2x16GB and tops at DDR5-6200 (while I definitely know there are people running DDR5-8000 there)? Did you have any problems with other capacities or speed? The "score" was measured with which CPU? Is there a difference for high-end/mid/low CPUs? Is there difference with different microcode versions (there is for sure for AMD)? There are way more questions than answers after looking at that list. Seriously, that "article" isn't useful at all. -

parkerthon I agree to an extent. I enjoy reading about AI which is no doubt why it’s a popular choice for content, but news summarizing news about how the AI industry is fairing is something I don’t come to Toms to read about. Someone needs to cover computer hardware more even if it’s niche. AI is, after all, heavily dependent on hardware even if it is all built for a microsoft/amazon/google data center.Reply -

apiltch After having worked on theReply

We have covered and continue to cover AI hardware. Please see the AI benchmarking story I did on various laptops last week:parkerthon said:I agree to an extent. I enjoy reading about AI which is no doubt why it’s a popular choice for content, but news summarizing news about how the AI industry is fairing is something I don’t come to Toms to read about. Someone needs to cover computer hardware more even if it’s niche. AI is, after all, heavily dependent on hardware even if it is all built for a microsoft/amazon/google data center.

https://www.tomshardware.com/laptops/i-tested-intels-meteor-lake-cpus-on-ai-workloads-and-amds-chips-sometimes-beat-them

I wouldn't call the current article a news summary as much as it's an op-ed on the problems with allowing software vendors to build their platforms on massive theft of copyrighted IP. This has serious implications for the future of computing. -

George³ Reply

Journalism copyright is under questions. What you saying IP? Unless the journalists and owners of the NY Tymes claim that they organized the events they cover.apiltch said:wouldn't call the current article a news summary as much as it's an op-ed on the problems with allowing software vendors to build their platforms on massive theft of copyrighted IP. -

coromonadalix anything published on the web now serve as a learning databaseReply

for sure Ai gurus will act as : now it's online, you have no control of it anymore, like facecrap and others

good luck putting strong regulations over that -

tamalero They were warned ages ago about this.Reply

And its going to be worse. We're entering the age of POST TRUTH.

Where truth will be almost impossible to distinguish itself from fabricated AI bull.

Everyone can be targeted, specially those with the money and means.

Like the surge of AI CP and deep fake sex videos. -

rabbit4me2 Goes to show you just like typical American behavior you can't have your cake and eat it too.Reply -

Alvar "Miles" Udell Getting around a paywall is different than reproducing the open web (open web defined as accessible without paying or requiring certain credentials). If I go to a certain article from TomsHardware, for example, I'm using an adblocker so I don't see ads, I use NoScript so dotmetrics, google-analytics, jwplatform, onesignal, parsley, permutive, and scorecardresearch are all blocked. If I ask Bing Copilot to reproduce the same article, I'm still not seeing any ads, I'm not triggering any of the other things, but I lack any images or charts which may be in the article. In both cases the website gets no monetary compensation from my visit. Compare this to a non-open website, even if ads and other content is blocked, they still get the paywall fee vs AI providing it to me for free and the website getting nothing.Reply

As for art and video, artists and creators for decades have been taking (sometimes not insubstantial amounts of) money from people to produce content, often pornographic, of copyrighted property without permission or a license, and often with the use of paid software, but I haven't seen studios and copyright owners sue the creators for taking $xxx to create a pornographic picture of (copyrighted character). AI is just allowing anyone to create content and not just professionals.

Most Popular